Venous Interventional Therapies

-Stents, Balloons, AVF, Laser, Ablation & Venous Filters

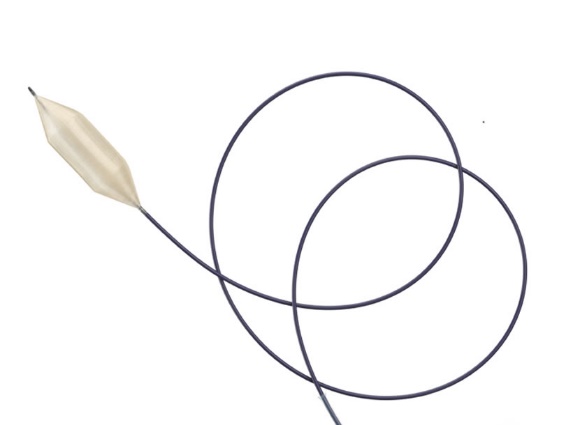

High Pressure Balloons –Conquest 4mm -10mm @40ATM & ATLAS GOLD 12mm -26mm@14-18ATM

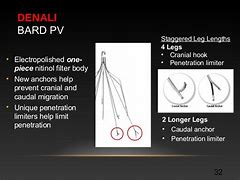

IVC Filters for PE & DVT- DENALI IVC FILTER

Venous Stents -Venovo venous stents (16mm -20mm x 80,100 & 140mm)

Compression Stockings- Sigvaris and VariCLose DVT Compression Stockings

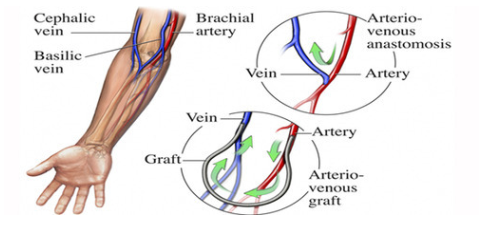

AV Fistula

An AV fistula is a connection, made by a vascular surgeon, of an artery to a vein. Arteries carry blood from the heart to the body, while veins carry blood from the body back to the heart.

Vascular surgeons specialize in blood vessel surgery and creation of AVF and arteriovenous grafts (AVG). AV F and AVG are typically placed in the forearm or upper arm.

if you are a dialysis patient with an AV fistula or graft as your access, over time it is possible that your AV fistula or graft may narrow or clot and require an interventional procedure to improve or restore the blood flow so that you can continue to receive dialysis.

If you are having problems with your access, your nephrologist may decide to refer you to a vascular care center for evaluation. There, the vascular specialist will determine if you need an interventional procedure, such as angioplasty, to ensure you leave the center with a fully functioning access.

Benefits of Angioplasty

Treating your dysfunctional access with angioplasty has many benefits:

- Blood flow to your AV fistula or graft is restored

- Minimal or no disruption in your normal dialysis schedule

- No surgery is required – a small skin puncture is made which will not require stitches

- General anesthesia is not required

- No hospital stay is involved

- Return to daily activities shortly after your procedure

Interventional radiologists, nephrologists, and vascular surgeons use minimally invasive procedures such as angioplasty and, if necessary, stent placement to restore blood flow and eliminate blockages of hemodialysis accesses, allowing you to continue your scheduled dialysis treatments and restore normal function to your access.

The tables on this website are converted with the Div Table online tool. Please subscribe for an online HTML editor membership to stop adding promotional messages to your documents.

Venous Thromboembolism (VTE)

Blood’s ability to clot helps keep you alive. Without it, every shaving nick and paper cut could turn into a medical emergency.But clotting can be a serious problem when it happens where it shouldn’t, like in your veins, where a clot can cut off your blood flow. That’s called a venous thromboembolism (VTE). VTEs are dangerous, but they’re treatable — and there’s a lot you can do to lower the odds you’ll get one.

Types of VTE

You may have never heard of a VTE before, but they’re common. There are two types, which are set apart by where they are in your body.

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT). As the name suggests, it develops deep in your veins, usually in the legs. You can get one in your arm, though. When this happens, your doctor may call it an upper-extremity DVT. It can cut off the flow of blood. DVTs can cause pain, swelling, redness, and warmth near the blocked vein.

- Pulmonary embolism (PE). This is more serious than a DVT. It usually happens when a DVT breaks loose and travels to your lungs. A pulmonary embolism is a life-threatening emergency. It can make it hard to breathe and cause a fast heart rate, chest pain, and dizziness. It can also cause you to become unconscious.

What Are the Symptoms?

DVT symptoms include:

- Pain or tenderness in your arm or leg, usually in the thigh or calf

- Swollen leg or arm

- Skin that’s red or warm to the touch

- Red streaks on the skin

With a pulmonary embolism, you could notice:

- Shortness of breath you can’t explain

- Fast breathing

- Chest pain under your rib cage that can get worse when you take a deep breath

- Rapid heart rate

- Feeling lightheaded or passing out

Medical treatments. Your odds for a VTE go up if you’re in the hospital for a while, get surgery (especially on your knees or hips), or have cancer treatments like chemotherapy.

Health conditions. Your VTE risk is higher if you have cancer, lupus or other immune problems, health conditions that make the blood thicker, or you’re obese.

Medications. Hormone replacement therapy and birth control pills can make it more likely you’ll get a VTE.

Your chances of a VTE also go up if you had an earlier VTE, stay in the same position for a long time, have a family history of blood clots, smoke, are pregnant, or you’re over 60.

Diagnosis

To rule out VTE, your doctor may perform this test:

D-dimer: This looks for levels of D-dimer, a substance that’s in your blood when you have a clot. If the test is normal, meaning your levels aren’t high and there’s no clot, you might not need any more tests.

If you do need more tests for DVT, you could get:

Duplex ultrasound. This painless imaging test doesn’t have radiation the way an X-ray does. It uses sound waves to create a picture of your legs. The doctor spreads warm gel on your skin, then rubs a wand over the area where she thinks the clot is. The wand sends sound waves into your body. The echoes go to a computer, which makes pictures of your blood vessels and sometimes the blood clots. A radiologist or someone who’s specially trained has to look at the images to explain what’s going on.

For a pulmonary embolism, you might also get:

Pulse oximetry: This is often the first test. The doctor will put a sensor on the end of your finger that measures the level of oxygen in your blood. A low level can mean a clot is preventing your blood from absorbing oxygen.

Arterial blood gas: The doctor takes blood from an artery to test the level of oxygen in it.

Chest X-ray: This test helps rule out a clot. They don’t show up on X-rays, but other conditions, like pneumonia or fluid in the lungs, do.

Ventilation perfusion (V/Q) scan: Doctors use this imaging test to check your lungs for air flow (ventilation, or V) and blood flow (perfusion, or Q).

Spiral computed tomography: This is a special version of a CT scan in which the scanner rotates to create a cross-section view of your lungs.

Pulmonary angiogram: If other imaging tests aren’t clear, doctors will use this test. Unlike the others, this test is invasive — the doctor will put a catheter into a vein and guide it to the veins and arteries around your heart. He’ll use it to inject a dye that shows up on an X-ray. This helps him see if there’s a clot in your lungs.

Echocardiogram: This ultrasound of the heart can help the doctor see areas that aren’t working the way they should. This test doesn’t diagnose PE, but it can show strain on the right side of your heart that results from PE.

VTE Treatment

If you have a VTE, you need to get it treated right away. Your doctor may talk to you about treatments like these:

Blood thinners. These drugs don’t break up the clot, but they can stop it from getting bigger so your body has time to break it down on its own. They include heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin, apixaban (Eliquis), edoxaban (Savaysa), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), and warfarin (Coumadin).

Clot-busting drugs. These medicines are injections that can break up your clot. They include drugs like tPA (tissue plasminogen activator).

Surgery. In some cases, your doctor may need to put a special filter into a vein, which can stop any future clots from getting to your lungs. Sometimes, people need surgery to remove a clot.

Even after you recover from a VTE and you’re out of the hospital, you’ll probably still need treatment with blood thinners for at least 3 months. That’s because your chances of having another VTE will be higher for a while.

VTE Prevention

There’s a lot you and your doctors can do to cut your odds of getting a VTE.

Here’s the most important thing: If you need to stay overnight in a hospital, ask your health care team about VTEs before you check in. Almost 2 out of 3 VTEs happen because of hospital visits. But if you get the right preventive treatment in the hospital, your risk can go way down.

If your health care team thinks you have a higher risk for a VTE — based on your medical history, health, and the type of treatment you’re getting — you may need:

- Blood thinners

- Compression stockings (special tight socks) that help with blood flow

- Intermittent pneumatic compression devices, which are kind of like blood pressure cuffs that automatically squeeze your legs to keep blood flowing

You may also need to get out of bed and walk around as soon as you can after treatment.

If you’ve had a VTE in the past, talk to your doctor about whether you need regular treatment to lower your chances of getting another.

There are also things that everyone can do to lower their chances of a VTE:

- Get regular exercise.

- Be at a healthy weight.

- If you smoke, quit.

And when you’re traveling, whether by train, plane, or car:

- Get up and walk around every 1 to 2 hours.

- Move around in your seat and stretch your legs often.

- Drink lots of fluids.

- Don’t smoke before your trip.

- Don’t drink alcohol, since it can dehydrate you.

- Don’t use medicines to make you sleep, so you’ll stay awake enough to move around.

- Ask your doctor if you should take an aspirin before a long plane flight.

What Causes DVT?

Many things can raise your chances of getting DVT. Here are some of the most common:

- Age. DVT can happen at any age, but your risk is greater after age 40.

- Sitting for long periods. When you sit for long stretches of time, the muscles in your lower legs stay lax. This makes it hard for blood to circulate, or move around, the way it should. Long flights or car rides can put you at risk.

- Bed rest, like when you’re in the hospital for a long time, can also keep your muscles still and raise your odds of DVT.

- Pregnancy . Carrying a baby puts more pressure on the veins in your legs and pelvis. What’s more, a clot can happen up to 6 weeks after you give birth.

- Obesity . People with a body mass index (BMI) over 30 have a higher chance of DVT. This measures how much body fat you have, compared with your height and weight.

- Serious health issues. Conditions like Irritable bowel disease, cancer, and heart disease can all raise your risk.

- Certain inherited blood disorders. Some diseases that run in families can make your blood thicker than normal or cause it to clot more than it should.

- Injury to a vein. This could result from a broken bone, surgery, or other trauma.

- Smoking makes blood cells stickier than they should be. It also harms the lining of your blood vessels. This makes it easier for clots to form.

- Birth control pills or hormone replacement therapy. The estrogen in these raises your blood’s ability to clot. (Progesterone-only pills don’t have the same risk.)

How Is DVT Treated?

Your doctor will want to stop the blood clot from getting bigger or breaking off and heading toward your lungs. She’ll also want to cut your chances of getting another DVT.

This can be done in one of three ways:

- Medicine. Blood thinners are the most common medications used to treat DVT. They cut your blood’s ability to clot. You may need to take them for 6 months. If your symptoms are severe or your clot is very large, your doctor may give you a strong medicine to dissolve it. These medications, called thrombolytics, have serious side effects like sudden bleeding. That’s why they’re not prescribed very often.

- Inferior vena cava (IVC) filter. If you can’t take a blood thinner or if one doesn’t help, your doctor may insert a small, cone-shaped filter inside your inferior vena cava. That’s the largest vein in your body. The filter can catch a large clot before it reaches your lungs.

- Compression stockings . These special socks are very tight at the ankle and get looser as they reach your knee. This pressure prevents blood from pooling in your veins. You can buy some types at the drugstore. But your doctor may prescribe a stronger version that must be fitted by an expert. The pressure created by the stockings pushes fluid up the leg, which allows blood to flow freely from the legs to the heart. Compression stockings not only improve blood flow, they also reduce swelling and pain. They are particularly recommended for DVT because the pressure stops blood from pooling and clotting.

Venous Ulcer & Lymphedema

A venous ulcer is a shallow skin wound that develops when the veins don’t return blood back toward the heart as they normally would. (This is venous insufficiency).

These ulcers usually develop on the sides of the lower leg, above the ankle and below the calf. Venous skin ulcers, also called stasis leg ulcers, heal slowly and often come back without preventative treatment.

What causes venous ulcers?

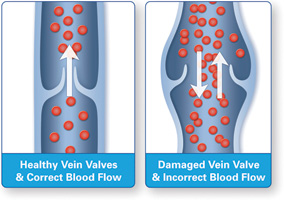

Veins have one-way valves that keep blood circulating to the heart. In venous insufficiency, the valves are damaged, and blood backs up and pools in the vein. The Blood may leak out of the vein and into the surrounding tissue, which can lead the tissue to break down and cause an ulcer.

What are the symptoms?

In the area where the blood is seeping out of the vein, the skin turns dark red or purple. Skin may also become thick, dry and itchy. Untreated, an ulcer may form and become painful. Legs may become swollen and sore. An infected wound may cause an odor, and puss may drain from the wound. The area around the wound also may be more tender and red.

It’s important to call us when you first see signs of a venous ulcer, as we may be able to help prevent the ulcer from forming. And, if it is formed, seek treatment immediately; smaller and newer ulcers heal faster.

How are venous skin ulcers diagnosed?

Drs. Sorenson and Lutz will ask questions about your health, and will examine affected areas. They may also perform ultrasound testing. All can be done within the comfort of the office. Doctor may use other tests to check for problems related to venous skin ulcers or to recheck the ulcer if it does not heal within a few weeks after starting treatment.

Velfour Four Layer Bandaging System for Treatment of Venous Leg Ulcers

Indication

– Venous leg ulcers, Lymphedema

– 4-layer bandaging system for treating venous leg ulcers & associated conditions

– Four kits are available which contains number of different components

Chronic Vein Disease Explained

What is Chronic Vein Disease (CVD)?

Chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) occurs when the valves in the leg veins are not working properly, causing blood to collect in the veins rather than return to the heart. This is called stasis.

Healthy veins contain valves which open and close to keep the blood moving in the right direction. Problems develop when some of those valves become damaged and stop working. This results in backward flow (“reflux”) of blood in the veins, and a slower drainage of the used blood from your legs. This is called Chronic Venous Disease (CVD).

What are the symptoms of Chronic Venous Disease?

Common signs of CVD in the legs include swelling, fatigue, pain, large visible veins, and in advanced cases, skin color changes, and even poorly healing wounds (ulceration’s).

- Leg pain

- Leg discomfort (itching/cramping/restless legs/heaviness)

- Leg fatigue

- Spider Veins

- Varicose Veins

- Swelling/ “Edema”

- Skin changes/ “Stasis Dermatitis”

- Ulceration

Who is at risk?

As much as 40 percent of people in the United States are estimated to have CVI. Some risk factors for CVD are genetic. These include family history, sex, and age. Risk increases for people over age 50 and the disease occurs more often in Women than Men. Other risk factors can be controlled. These include obesity, pregnancy, having a job that requires prolonged sitting or standing, injury, surgery, and blood clots.

- Family History

- Sex (Females have more risk)

- Age (Risk increases with age)

- Obesity

- Pregnancy

- Prolonged standing or sitting

- Prior injury or surgery

- History of blood clot

How is CVD treated?

The first step in management is an accurate diagnosis performed by a trained professional using non-invasive doppler ultrasound. Following diagnosis most insurance will require a trial of conservative measures like wearing medical grade compression stockings / hose. If the problem is not improved, minimally-invasive procedures, performed in the comfort of our office may be needed.

Treatment Overview:

- Conservative measures

- Radiofrequency (RF) Ablation

- Endovenous Laser Treatment (EVLT)

- Ultrasound Guided Foam Sclerotherapy (USGS)

- Micro phlebectomy

- Visual Sclerotherapy

- Angie Thermocoagulation

Lymphedema

What is Lymphedema?

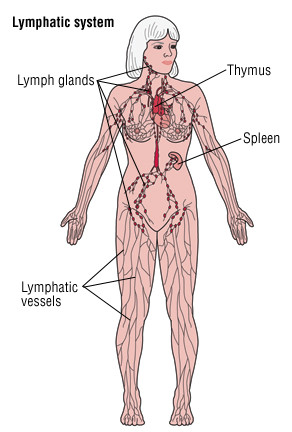

Lymphedema is the buildup of fluid called lymph in the tissues under your skin when something blocks its normal flow. This causes swelling, most commonly in an arm or leg.

Lymph normally does an important job for your body. It carries foreign material and bacteria away from your skin and body tissues, and it circulates infection-fighting cells that are part of your immune system.

Lymph flows slowly through the network of vessels called your lymphatic system. Lymph flow stops at points along the way to be filtered through lymph nodes. Lymph nodes are small bean-shaped organs that are part of your immune system.

Lymph is formed from the fluid that surrounds cells in the body. It makes its way into very small lymphatic vessels. After traveling through these small vessels, lymph drains into deeper, wider lymph channels that run through the body. Eventually, lymph fluid returns to the blood.

Lymphedema occurs when there is inadequate lymph drainage from the body, usually from a blockage in a lymph channel. Lymphatic fluid builds up underneath the skin and causes swelling. Most commonly lymphedema affects the arms or legs.

Swelling from lymphedema can look similar to the more common edema caused by leakage from tiny blood vessels under the skin.

In most cases of lymphedema, the lymphatic system has been injured so that the flow of lymph is blocked either temporarily or permanently. This is called secondary lymphedema. Common causes include:

- Surgical damage — Surgical cuts and the removal of lymph nodes can interfere with normal lymph flow. Sometimes, lymphedema appears immediately after surgery and goes away quickly. In other cases, lymphedema develops from one month to 15 years after a surgical procedure. Lymphedema occurs quite often in women who have had multiple lymph nodes removed during surgery for breast cancer.

- An infection involving the lymphatic vessels — An infection that involves the lymphatic vessels can be severe enough to cause lymphedema. In areas of the tropics and subtropics, such as South American, the Caribbean, Africa, Asia and the South Pacific, parasites are a common cause of lymphedema. Filariasis, a parasitic worm infection, blocks the lymph channels and causes swelling and thickening below the skin, usually in the legs.

- Cancer — Lymphoma, a cancer that starts in the lymph nodes, or other types of cancer that spread to the lymph nodes may block lymph vessels.

- Radiation therapy for cancer — This treatment can cause scar tissue to develop and block the lymphatic vessels.

When lymphedema occurs without any known injury or infection, it is called primary lymphedema. Doctors diagnose three types of primary lymphedema according to when symptoms first appear:

- At birth — Also known as congenital lymphedema. Risk is higher in female newborns. The legs are affected more often than the arms. Usually both legs are swollen.

- After birth but before age 36 — Usually, it is first noted during the early teenage years. This is the most common type of primary lymphedema.

- Age 36 and older — This is the rarest type of primary lymphedema.

All three types of primary lymphedema are probably related to the abnormal development of lymph channels before birth. The difference is when in life they first cause swelling of the legs or arms.

Symptoms

Lymphedema causes swelling with a feeling of heaviness, tightness or fullness, usually in an arm or leg. In most cases, only one arm or leg is affected. Swelling in the leg usually begins at the foot, and then moves up if it worsens to include the ankle, calf and knee. Additional symptoms can include:

- A dull ache in the affected limb

- A feeling of tightness in the skin of the affected limb

- Difficulty moving a limb or bending at a joint because of swelling and skin tightness

- Shoes, rings or watches that suddenly feel too tight

Lymphedema can make it easier to develop a skin infection. Signs of infection include fever, pain, heat and redness. If lymphedema becomes chronic (long lasting), the skin in the affected area often becomes thickened and hard.

Diagnosis

Your doctor will ask you whether you have had any surgery, radiation treatments, or infections in the affected area. The doctor may ask if you have ever had a blood clot. If a child has lymphedema, the doctor will ask if anyone in your family had leg swelling starting at a young age. This may indicate an inherited disorder.

Your doctor will examine the swollen area and press on the affected skin to look for a fingertip indentation (pitting). The skin will be indented in people with the much more common type of edema caused by leaky blood vessels. Pitting does not happen when you press on skin if you have lymphedema.

Your doctor may measure the circumference of the affected arm or leg to determine how swollen it is compared to the other one. The doctor will look for signs of infection, including fever, redness, warmth and tenderness.

Usually, no specific testing is necessary to diagnose lymphedema. But tests may be ordered if the diagnosis is not clear or there is no obvious cause for your condition:

- A blood count can look for a high level of white cells, which means you might have an infection.

- An ultrasound can look for blood clots, which can cause an arm or leg to swell.

- A computed tomography (CT) scan looks for a mass or tumor that could be blocking lymph vessels in the swollen arm or leg.