Visceral Therapies

Celiac Artery Intervention

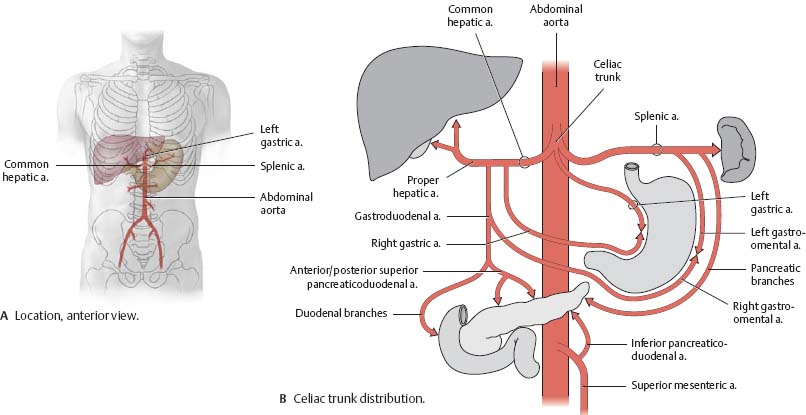

Celiac artery, also known as the celiac axis or celiac trunk, is a major visceral artery in the abdominal cavity supplying the foregut. It arises from the abdominal aorta and commonly gives rise to three branches: left gastric artery, splenic artery, and common hepatic artery.

The celiac artery (or the celiac trunk) provides oxygenated blood to the foregut: it supplies blood to the stomach, the liver, the spleen and the part of the esophagus that reaches into the abdomen. It also supplies the superior (or upper) half of the duodenum and the pancreas.

Celiac artery stenosis–also known as celiac artery compression syndrome–is an unusual abnormality that results in a severe decrease in the amount of blood that reaches the stomach and abdominal region. Seen most often in young, underweight women, celiac artery stenosis sufferers display a number of distinct symptoms.

The most common symptoms of celiac artery stenosis are gastrointestinal and include abdominal pain after eating, often severe weight loss and a sharp, persistent pain in the upper section of the abdomen.

Superior Mesenteric Artery Intervention

The gastrointestinal tract is supplied by the celiac trunk, the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), and the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA). The celiac trunk originates from the anterior aorta just below the diaphragm at the level of the thoracic vertebrae 12 (T12) or the first lumbar vertebra. It branches into the common hepatic, splenic, and left gastric arteries.

Mesenteric artery stenosis results in insufficient blood flow to the small intestine, causing intestinal ischemia. Chronic mesenteric ischemia is usually due to atherosclerosis, but is rarely caused by extensive fibromuscular disease or trauma.

The celiac trunk, SMA, and IMA usually have ostial disease and occlusions are typically found in the proximal few centimeters of these arteries. Chronic mesenteric ischemia results when at least two of the three major splanchnic arteries have severe stenosis. The SMA is almost always involved in symptomatic cases. At rest, patients have sufficient intestinal blood flow to maintain gut viability and prevent symptom development. However, the increased demand on mesenteric circulation after a meal may overwhelm the compensatory ability of the collateral circulation, thereby causing postprandial intestinal angina.

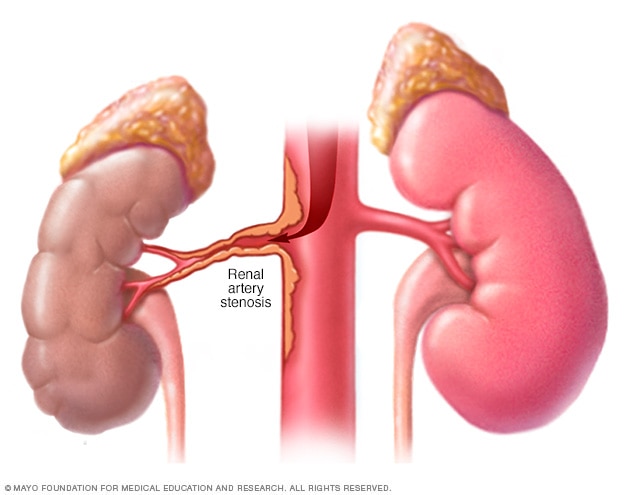

Renal Artery Intervention

Renal artery stenosis is the narrowing of one or more arteries that carry blood to your kidneys (renal arteries). Narrowing of the arteries prevents normal amounts of oxygen-rich blood from reaching your kidneys. Your kidneys need adequate blood flow to help filter waste products and remove excess fluids. Reduced blood flow may increase blood pressure in your whole body (systemic blood pressure or hypertension) and injure kidney tissue.

Symptoms

Renal artery stenosis often doesn’t cause any signs or symptoms until it’s advanced. The condition may be discovered incidentally during testing for something else. Your doctor may also suspect a problem if you have:

High blood pressure that begins suddenly or worsens without explanation

High blood pressure that begins before age 30 or after age 50

As renal artery stenosis progresses, other signs and symptoms may include:

High blood pressure that’s hard to control

A whooshing sound as blood flows through a narrowed vessel (bruit), which your doctor hears through a stethoscope placed over your kidneys

Elevated protein levels in the urine or other signs of abnormal kidney function

Worsening kidney function during treatment for high blood pressure

Fluid overload and swelling in your body’s tissues

Treatment-resistant heart failure